Untrammeled Quality Indicators

Monitoring the Untrammeled Quality assesses how management of a wilderness is trending over time toward more or less human manipulation of plant communities, fish and wildlife populations, insects and disease, soil and water resources, and fire processes. Key indicators and measures monitor actions that are either authorized or unauthorized intentional manipulations of the biophysical environment. This section first provides guidance on what a trammeling action is (section 2.1) and then describes detailed protocols for monitoring the following indicators and measures:

- 2.2 Indicator: Actions Authorized by the Federal Land Manager that Intentionally Manipulate the Biophysical Environment

- 2.2.1 Measure: Number of authorized actions and persistent structures designed to manipulate plants, animals, pathogens, soil, water, or fire.

- 2.3 Indicator: Actions Not Authorized by the Federal Land Manager that Intentionally Manipulate the Biophysical Environment

- 2.3.1 Measure: Number of unauthorized actions and persistent structures by agencies, organizations, or individuals that manipulate plants, animals, pathogens, soil, water, or fire.

2.1 What is a Trammeling Action?

This section provides guidelines and examples to clarify what is and is not a trammeling action, based on the recommendations in Keeping It Wild 2 (Landres et al. 2015). These guidelines and examples should be sufficient to help staff decide most of the cases whether an action is a trammeling or not and provide sufficient guidance for local units to determine novel and rarer cases as they occur. A trammeling action is defined as an action or persistent structure that intentionally manipulates "the earth and its community of life" inside a designated wilderness or inside an area that, by Congressional legislation or agency policy, is managed to preserve wilderness character.

The following terms and phrases clarify the trammeling action definition described above:

- Intentional—An action done on purpose, deliberately, or willfully.

- Manipulation—An action that alters, hinders, restricts, controls, or manipulates "the earth and its community of life" including the type, amount, or distribution of plants, animals, or physical resources.

- Intentional manipulation—An action that purposefully alters, hinders, restricts, controls, or manipulates "the earth and its community of life."

Two concepts are crucial for understanding what is, and is not a trammeling action: (1) restraint and (2) intention. The first concept, restraining our power to manipulate or control "the earth and its community of life," is at the core of the Untrammeled Quality of wilderness character. Wilderness legislation and policies mandate that federal land managers exercise restraint when authorizing actions that interfere with or control wilderness ecosystems. While other agencies, organizations, and the public are not beholden to these same restraints, activities not authorized by the federal land manager that manipulate the wilderness environment are counted as trammeling actions.

The second concept central to the idea of trammeling is intentionality. Actions that deliberately interfere with, manage, or control an aspect of wilderness ecosystems are intentional and clear instances of trammeling. Section 2.0 of this technical guide, Untrammeled Quality, explains that intentional actions are counted as a trammeling regardless of the magnitude of their effects (including aerial extent, intensity, and duration). For pragmatic reasons, however, some actions are not monitored if they fall below a minimum practical threshold of scale and scope (e.g., hand pulling a few individual nonindigenous invasive plants). In general, when such actions have substantial and foreseeable effects on a wilderness ecosystem, they are counted as a trammeling, as shown in figure 2.2.1 in section 2.1.4 in part 2.

Actions initiated outside the boundaries of a designated wilderness generally do not affect the Untrammeled Quality. However, some actions taken outside of wilderness boundaries do intentionally alter, hinder, restrict, control, or manipulate the "the earth and its community of life" within wilderness. Examples include, but are not limited to, the introduction of game species outside a wilderness with the intention that the animals will occupy habitat within a wilderness, ignition of fire outside of wilderness with the anticipation that fire will burn into wilderness, installation of a dam outside of a wilderness boundary that results in the containment of a watershed within wilderness, or seeding of clouds for weather manipulation over wilderness.

This section describes three types of activities:

- Activities that are trammeling actions

- Activities that are not trammeling actions

- Activities that may be trammeling actions

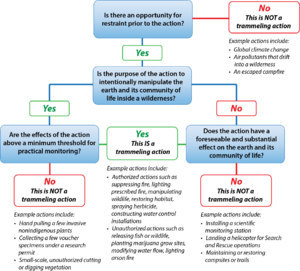

At the end of this section, a flowchart provides general guidance for making determinations about the three types of activities. Additionally, line officers often make (difficult) decisions to exercise restraint and not take action in wilderness, despite a perceived need. Decisions to not take action in wilderness are not explicitly monitored under this quality, but would be reflected in a lower overall tally of intentional actions taken in wilderness, which equates to less impact to the Untrammeled Quality.

2.1.1 Activities That Are Trammeling Actions

There are two broad classes of trammeling actions: (1) those authorized by the federal land manager, and (2) those that are not. Three subclasses under each broad class reflect whether the action is taken on (a) a biological resource, (b) a physical resource, or (c) a resource outside a wilderness with the intent to manipulate biophysical resources within a wilderness.

Agency authorized trammeling actions are actions that are authorized by the Forest Service as well as actions by other agencies, organizations, or individuals that have been approved or permitted by the Forest Service.

- Examples of actions taken inside wilderness on a biological resource to intentionally affect "the earth and its community of life" include the following:

- Administrative actions to remove or kill indigenous or nonindigenous vegetation, fish, or wildlife.

- Adding or restoring indigenous or nonindigenous vegetation, fish, or wildlife.

- Using chemicals or biocontrol agents to control indigenous or nonindigenous vegetation, fish, or wildlife.

- Collecting, capturing, or releasing fish and wildlife under a research permit.

- Enclosing or excluding fish and wildlife from an area.

- Permitting livestock grazing.

- Examples of actions taken inside wilderness on a physical resource or natural process to intentionally affect "the earth and its community of life" include the following:

- Taking suppression action on naturally ignited fire.

- Igniting fire (under management prescription) for any purpose.

- Constructing or maintaining a dam, water diversion, guzzler, fish barrier, or other persistent installation intended to continuously alter wilderness hydrology.

- Installing a bat gate on a cave or constructing fencing to an extent sufficient to alter wildlife behavior (e.g., elk or cattle exclosures).

- Adding acid-buffering limestone to water to neutralize the effects of acid deposition.

- Collecting fossils, rocks, paleontological specimens under a collection or research permit.

- Implementing Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) activities.

- Examples of actions taken outside wilderness on a physical or biological resource or process to intentionally affect "the earth and its community of life" inside a wilderness include the following:

- Cloud seeding to intentionally increase precipitation inside wilderness.

- Damming a river outside a wilderness to intentionally alter the hydrology inside wilderness.

- Killing fish and wildlife outside wilderness, or planting or stocking fish or wildlife outside wilderness, to intentionally affect the population or distribution of this species inside wilderness.

Unauthorized trammeling actions are actions taken by other agencies, organizations, or individuals that the federal land manager has not authorized, approved, or permitted.

- Examples of actions taken inside wilderness on a biological resource to intentionally affect "the earth and its community of life" include the following:

- Unauthorized removal of or killing indigenous or nonindigenous vegetation, fish, or wildlife with the intent of altering distribution or population dynamics (e.g., predator control).

- Unauthorized addition or restoration of indigenous or nonindigenous vegetation, fish, or wildlife.

- Indirect manipulation of fish and wildlife, such as changing hunting regulations with the goal of decreasing predator populations within wilderness.

- Illegal livestock grazing, provided that there is reasonable certainty that grazing activities in wilderness were intentional as opposed to unintentional (e.g., resulting from poorly maintained fencing).

- Examples of actions taken inside wilderness on a physical resource or natural process to intentionally affect "the earth and its community of life" include the following:

- Setting arson fire.

- Modifying water resources to provide water for wildlife, or otherwise store water or alter the timing of water flow.

- Examples of actions taken outside wilderness on a physical or biological resource to intentionally affect "the earth and its community of life" inside a wilderness includes the following:

- Killing individual animals outside of wilderness with the intention to affect populations whose ranges expand into wilderness.

- Releasing individual animals outside of wilderness with the intention to affect populations whose ranges expand into wilderness.

In some situations, Forest Service land managers may assume that they do not have an opportunity for restraint because an action is required to comply with other laws or agency policies, or to protect human life or property. Examples of such situations include restoring habitat for a listed endangered species, spraying herbicides to eradicate an invasive nonindigenous plant that is degrading wildlife habitat, transplanting an extirpated species back into a wilderness, or suppressing a naturally ignited fire. These are still considered trammeling actions because even in these situations there is a decision to take action, as well as a decision about the type and intensity of action.

2.1.2 Activities That Are Not Trammeling Actions

Actions for which there is no opportunity for restraint are not considered a trammeling. For example, climate change, air pollutants drifting into a wilderness, and the presence of nonindigenous species that naturally dispersed into a wilderness are not the result of deliberate decisions or actions, and therefore, do not provide an opportunity for restraint. Accidental unauthorized actions, such as escaped campfires and oils spills, similarly lack an opportunity to restrain individuals' power over the landscape. Past actions that manipulated the biophysical environment before the designation of the area as wilderness are not considered a trammeling because the provisions of the 1964 Wilderness Act did not apply to the area prior to designation.

Another group of examples that are not a trammeling encompass those small-scale actions with no intent to manipulate "the earth and its community of life," such as installing meteorological or other science instrumentation, landing a helicopter for search and rescue operations, and removing trash. Camping violations, incidental development of campsites, unauthorized motorized incursions, littering, and other illegal activities not intended to manipulate the biophysical environment also are not counted as trammeling actions because legality is irrelevant in determining whether an action is a trammeling.

Hunting, for sport or subsistence, has provoked an enormous amount of interagency discussion about whether it degrades the Untrammeled Quality. The general interagency consensus is that hunting is not a trammeling action because individual hunters are taking individual animals without the intention to manipulate the wildlife population. However, if a state wildlife agency increases predator bag limits in a wilderness to purposefully alter the predator-prey relationship to maximize the viability of a game species, this manipulation of the "community of life" would degrade the Untrammeled Quality.

2.1.3 Activities That May Be Trammeling Actions

There are two types of actions that may or may not be considered trammeling actions. The first includes intentional manipulations that interfere with or control an aspect of wilderness ecosystems but are too small in scale or scope to be practically monitored. The second type encompasses those nuanced cases where the primary purpose of the action is not to manipulate the ecosystem, but a foreseeable and substantial effect on the earth and its community is required to achieve this purpose. This second type of action can be confusing because it still results in intentional manipulations of the biophysical environment even though that was not the primary purpose. As shown in table 2.2.1, several example situations illustrate how an action may or may not be a trammeling, depending on the extent of the action and its effects. The table columns "Likely Not a Trammeling" and "Likely a Trammeling" present situations where the action being taken would not, or would be considered a trammeling.

2.1.4 Trammeling Flowchart

The flowchart depicted in figure 2.2.1 provides general guidelines using a series of questions to help agency staff determine when an action should be considered a trammeling. The first question asks if there is an opportunity for restraint, and is placed first to help avoid confusing those actions that are beyond the scope of management control, or are unauthorized accidents, from actions that Forest Service land managers or others do have an opportunity to influence. Political considerations are not a factor in determining whether or not there is an opportunity for restraint. The second question examines the intentionality of the action and whether the purpose is to manipulate "the earth and its community of life." If there is a clear intent to manipulate, then the action is counted as a trammeling unless it does not meet a minimum threshold for practicable monitoring. If the purpose of the activity is not to manipulate the ecological system, the action is nonetheless considered a trammeling if it results in foreseeable and substantial effects to the wilderness ecosystem.

2.2 Indicator: Actions Authorized by the Federal Land Manager that Intentionally Manipulate the Biophysical Environment

This indicator focuses on actions and persistent structures authorized by the agency that intentionally manipulate the biophysical environment. There is one required measure for this indicator.

2.2.1 Measure: Number of Authorized Actions and Persistent Structures Designed to Manipulate Plants, Animals, Pathogens, Soil, Water, or Fire

This measure assesses the 3-year rolling average of authorized trammeling actions, based on an annual count of authorized actions and persistent structures intended to manipulate any component of the biophysical environment within wilderness (including vegetation, fish, wildlife, insects, pathogens, soil, water, or fire). Local data are compiled and entered in NRM-WCM annually. NRM-WCM calculates the annual value, and the WCMD then calculates the 3-year rolling average (the measure value). Table 2.2.2 describes the key tasks for this measure.

Protocol

Step 1: Ensure users understand what constitutes authorized trammeling and then compile data. Detailed information about how to determine what is, is not, and may be a trammeling action, including numerous examples, can be found in section 2.1 in part 2. This measure includes discretionary and non-discretionary actions required to uphold Federal law, including those explicitly allowed under the Wilderness Act and subsequent wilderness legislation. For example, permitted livestock grazing authorized by the designating legislation for a wilderness is counted as a trammeling action. Intentional manipulations taken by other federal agencies, tribal or state agencies, organizations, and private citizens are also included under this measure if these actions are authorized by the Forest Service. This includes actions authorized through special use permits (SUPs) or other instruments (e.g., research actions, state fish and wildlife management actions).

Due to the wide variety of types of actions counted under this measure, there is no single source for data. The complexity of data compilation for this measure depends on the size of a given wilderness, its location, whether its management is shared with another district, forest, or agency, and on other factors that may not be predictable on a year-to-year basis. A recommended starting point in the compilation of data for this measure is to coordinate with wilderness rangers, wilderness managers, forest and district specialists, and the unit line officer to compile a list of readily known actions (including persistent structures), and to gauge the level of confidence that this list is comprehensive. If this initial list of actions is not comprehensive, other potential data sources to confirm whether or not additional actions were implemented include minimum requirements analyses (MRA), National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) documents, Pesticide Use Proposals, SUPs, fire narratives, (ICS-209 forms), Forest Service corporate databases (e.g., NRM-Wilderness, Forest Service Activity Tracking System [FACTS], Project Activity Levels [PALS], Fire Statistics System [FIRESTAT], Wildland Fire Decision Support System [WFDSS]), and state agency records.

Step 2: Count the number of authorized trammeling actions that occurred during the fiscal year. Where questions arise as to whether a seemingly inconsequential action truly manipulates "the earth and its community of life," the scale of an action can help determine whether or not the action constitutes trammeling. If the magnitude of an action's consequences will exceed a certain threshold, the action is counted as a trammeling. All trammeling actions that cross this threshold are counted equally, regardless of the extent of their effects (e.g., spraying herbicide on a small population of noxious weeds is equivalent to spraying herbicide across 1,000 acres; an herbicide treatment of weeds targeting one species is equivalent to an herbicide treatment targeting five species simultaneously). Below the established threshold, actions are not considered to be of sufficient magnitude to be counted as a trammeling for this monitoring effort (e.g., hand pulling a small number of invasive plants, removing a downed tree across a trail, or restoring a campsite).

The counting protocol for authorized trammeling actions is as follows, with counting instructions grouped in categories including scale of action, timing of action, location of action, fire-related actions, persistent structures, and other clarifications:

- Scale of Action

- Only count actions that are of sufficient scale to qualify as trammeling actions for practicable monitoring, as described above and in section 2.1 in part 2.

- All actions that meet the scale requirements for monitoring trammeling actions are counted equally, regardless of the magnitude of their effects.

- Actions that are individually too small in scale to be counted as trammeling actions are considered a trammeling if their cumulative effects crossed the threshold described above and in section 2.1 in part 2. For instance, removing a single hazard tree in a campsite is not considered a trammeling. However, an insect or disease event that killed many trees in an area with many campsites and resulted in the removal of a large number of hazard trees could be considered a trammeling. Local units must use their discretion and judgment in determining when cumulative effects cross the threshold resulting in a series of otherwise minor actions constituting a trammeling, including whether subsequent yet discrete actions add to these cumulative effects and constitute additional trammeling actions.

- Timing of Action

- Ongoing, multi-year actions are counted once annually per fiscal year.

- A single action that incidentally spans the fiscal year is only counted as a trammeling action for the initial fiscal year. For example, a watershed stabilization project implemented between September 15 and October 15, 2015, counts as one action for fiscal year 2019 and zero actions for fiscal year 2020.

- Location of Action

- The decision to take an action that occurs simultaneously in multiple locations in a wilderness is counted as a single action. For example, treatments of discrete invasive species populations located in different areas using herbicide counts as a single action. Similarly, concurrently stocking fish in multiple lakes across a wilderness counts as a single trammeling action.

- Actions that occur outside of wilderness with the explicit intent of manipulating the biophysical environment within wilderness count as trammeling actions.

- Fire-related Actions

- Management or suppression of a wildfire —whether naturally ignited or human-caused—counts as a single trammeling action per fire, regardless of the number or type of fire management actions taken. Types of fire management actions may include:

- Fireline construction (handline, tree felling, explosives, dozer line, wet line, leaf blowers, sprinkler systems, or mechanical clearing of safety zones).

- Burn operations (backfiring, burn outs, or black lining).

- Extinguishing fire (use of water, dirt, or flappers).

- Application of fire retardant.

- Management or suppression of a wildfire —whether naturally ignited or human-caused—counts as a single trammeling action per fire, regardless of the number or type of fire management actions taken. Types of fire management actions may include:

For example, suppression of a single wildfire by constructing a fireline and conducting burn operations during the course of the incident would count as one trammeling action. However, the construction of a fireline on two discrete wildfires in a wilderness in the same fiscal year counts as two trammeling actions.

- The issue of scale described in section 2.1 does not apply to management of wildfire because seemingly minor attempts to alter the behavior of a natural fire can have significant consequences. For instance, cutting down and suppressing a burning snag started by lightning—an action that is seemingly small in scale— may prevent a natural fire that otherwise may burn thousands of acres. Note, however, that actions taken on campfires that are not yet wildfires do not count as trammeling actions. For example, putting out an abandoned campfire that is still contained within a fire ring as part of routine wilderness maintenance would not count as a trammeling action.

- Suppression of a fire adjacent to but outside of wilderness constitutes a trammeling action when there is reasonable certainty that it would have likely burned into wilderness absent any suppression action (given factors such as slope, terrain, fuels, weather, fire behavior, and specific suppression actions taken) and when the action is taken with the explicit intent of preventing or limiting fire within wilderness. For example, suppression action taken on a fire 20 miles from the wilderness boundary may count as a trammeling action if conditions are extremely dry and there are high winds in the direction of the wilderness. In contrast, suppression action taken on a creeping fire in leaf litter 75 feet from the wilderness boundary may not count as a trammeling action if there's 78% percent humidity and it is unlikely the fire will spread.

- The use of prescribed fire, regardless of the tactics used to manage the burn, counts as a single trammeling action because of the decision to intervene in natural processes in accordance with the management prescription developed by the agency. The implementation of multiple prescribed fires in a wilderness in a single fiscal year also counts as a single trammeling action if each burn was authorized via the same burn plan. Prescribed fires conducted in the same fiscal year authorized by multiple burn plans—for instance in a wilderness managed by two Forest Service regions or forests—counts as multiple trammeling actions.

- Different types of BAER treatments—where they pass the threshold for scale— constitute separate trammeling actions for each incident they are associated with.

- Persistent Structures

- To be counted as a trammeling action, a persistent structure must be intended to purposefully alter, hinder, restrict, control, or manipulate the "the earth and its community of life." Examples of persistent structures that would be counted under this measure include, but are not limited to fish barriers, dams, water diversions, guzzlers, bat gates, or fencing (e.g., wildlife or cattle enclosure areas). Each unique persistent structure that manipulates any component of the biophysical environment is counted for each year that it exists.

- An action to install a persistent structure that alters the biophysical environment in wilderness is counted once as a trammeling in the year that the installation occurred and once per year subsequently, as long as the structure persists. The installation and existence of the structure in the first year are not double counted as two trammeling actions. Persistent structures that are no longer functioning as intended are not counted as a trammeling if it can be demonstrated they do not alter or manipulate any component of the biophysical environment (e.g., fencing previously used to form a cattle exclosure that has fallen down).

- Other Clarifications

- Single projects or decisions that involve related yet distinct actions count as multiple trammeling actions. For example, a stream restoration project that involves both the release of piscicide and restocking native fish count as two trammeling actions. Treating one or more species of invasive plants with herbicide and a biological control agent also count as two trammeling actions—one action for the use of herbicide, and one action for the release of the biological control agent. The number of species affected by each treatment is incidental.

- Actions intended to manipulate the biophysical environment within wilderness that are unsuccessful are still counted as trammeling actions.'

Step 3: Enter data in NRM and the WCMD. Track trammeling actions annually and enter them into the NRM-WCM application for each fiscal year. NRM-WCM will sum the counts of all authorized trammeling actions to generate an annual value. Local units must then validate the value generated by NRM-WCM and correct records in NRM as necessary. Once validated, enter the annual value in the WCMD. The WCMD automatically calculates 3-year rolling averages based on the annual values. The measure value is the 3-year rolling average number of trammeling actions.

Caveats and Cautions

When a unit experiences a large wildfire managed by an Incident Management Team, these data can be difficult to obtain. Units are therefore encouraged to seek out data on trammeling actions during or soon after the incident. In addition, interpretation of the number of trammeling actions associated with an action or decision—in particular with fire management, and occasionally with other types of management actions—may vary due to the potential complexity of determining what constitutes a trammeling action. Units should therefore provide a narrative in the WCMD describing the methodology and considerations behind any nuanced or complex trammeling interpretations.

When deciding which specific 3 years of data to include to calculate the rolling average for this measure, always defer to the highest data adequacy available (section 1.2.3 in part 2). Ideally the data with the highest degree of adequacy will also be the most recent data collected, but this might not always be the case.

Data Adequacy

Data adequacy is typically medium to high, though this should be verified and documented locally. In many cases it is likely that all data records related to authorized actions and persistent structures that manipulate the biophysical environment can be gathered, although this may be difficult for large wildernesses or wildernesses managed by more than one forest or Forest Service region. Data quantity is therefore often complete and data quality is good.

Frequency

Data are compiled, analyzed, and entered into the WCMD annually due to the variable nature of trammeling actions.

Threshold for Change

The threshold for meaningful change is a 5-percent change in the 3-year rolling average number of authorized actions and persistent structures. Once there are five measure values, the threshold for meaningful change will switch to regression analysis. A decrease in the 3-year rolling average beyond the threshold for meaningful change results in an improving trend in this measure.

2.3 Indicator: Actions Not Authorized by the Federal Land Manager that Intentionally Manipulate the Biophysical Environment

This indicator focuses on actions that are not authorized by the agency, but that intentionally manipulate ecological systems in wilderness. There is one required measure for this indicator.

2.3.1 Measure: Number of Unauthorized Actions and Persistent Structures by Agencies, Organizations, or Individuals That Manipulate Plants, Animals, Pathogens, Soil, Water, or Fire

This measure assesses the 3-year rolling average of unauthorized trammeling actions based on an annual count of known actions not authorized by the Forest Service taken by other federal and state agencies, organizations, or individuals that are intended to manipulate any component of the biophysical environment within wilderness (including vegetation, fish, wildlife, insects, pathogens, soil, water, or fire). Local data are compiled and entered in NRM-WCM annually. NRM-WCM calculates the annual value, and the WCMD then calculates the 3-year rolling average (the measure value). Table 2.2.3 describes key features for this measure.

Protocol

Step 1: Ensure users understand what constitutes unauthorized trammeling and then compile data. Section 2.1 provides detailed information about how to determine what is, is not, and may be a trammeling action, including numerous examples. Unauthorized trammeling actions may be taken by different branches of the Forest Service, other federal agencies, tribal and state agencies, organizations, or private citizens. Actions taken by state or other government agencies with the knowledge and approval of the Forest Service through a SUP or cooperative agreement are considered authorized actions and counted under the measure Number of Authorized Actions and Persistent Structures Designed to Manipulate Plants, Animals, Pathogens, Soil, Water, or Fire (see section 2.2.1 in part 2). Actions taken by states or other government agencies with the knowledge of the Forest Service but without explicit approval through a SUP or another instrument are counted under this measure.

Due to the wide variety of types of actions counted under this measure, there is no single source for data. The complexity of data compilation for this measure depends on the size of a given wilderness, its location, and whether its management is shared with another local unit, national forest, or federal agency. The complexity is also influenced by the fact that unauthorized actions are not predictable on a year-to-year basis, and unauthorized actions often go unreported or even undiscovered.

A recommended starting point in the compilation of data for this measure is to coordinate with wilderness rangers, wilderness managers, interdisciplinary team members, law enforcement, and the local unit line officer to compile a list of readily known unauthorized actions and persistent structures, and to gauge the level of confidence that the list is comprehensive. Other potential data sources include the Forest Service Law Enforcement and Investigations Management Attainment Reporting System (LEIMARS), state agency records, partner or watchdog organizations, and volunteers.

Step 2: Count the number of unauthorized trammeling actions that occurred during the fiscal year. Where questions arise as to whether a seemingly inconsequential action truly manipulates "the earth and its community of life," the scale of an action can help determine whether or not the action constitutes trammeling. If the magnitude of an action's consequences will exceed a certain threshold, the action is counted as a trammeling. All trammeling actions that cross this threshold are counted equally, regardless of the extent of their effects. Below the established threshold, actions are not considered to be of sufficient magnitude to be counted as a trammeling for this monitoring effort.

The counting protocol for unauthorized trammeling actions is as follows, with counting instructions grouped in categories including scale of action, timing of action, location of action, persistent structures, and other clarifications:

- Scale of Action

- Only count actions that are of sufficient scale to qualify as trammeling actions for practicable monitoring, as described above and in section 2.1 in part 2.

- All actions that meet the scale requirements for monitoring trammeling actions are counted equally, regardless of the magnitude of their effects. Due to the uncertainty as to who is responsible for a given trammeling action, evidence of each unauthorized trammeling action that is discovered at different times or in different places is counted as a distinct trammeling action.

- Actions taken by a single individual or entity that are individually too small in scale to be counted as trammeling actions are considered a trammeling action if their cumulative effects crossed the threshold described above and in section 2.1 in part 2. For instance, illegal cutting of a single tree is not considered a trammeling action. However, illegal theft of timber over a larger area or the illegal cutting of a ski run may be considered trammeling actions. Local units must use discretion and judgment in determining when cumulative effects cross the threshold resulting in a series of otherwise minor actions constituting a trammeling, including whether subsequent yet discrete actions add to these cumulative effects and constitute additional trammeling actions.

- Timing of Action

- Ongoing, multi-year unauthorized actions are counted once annually per fiscal year (e.g., marijuana cultivation or repeated unauthorized state fish and game agency management actions).

- Location of Action

- Unauthorized actions taken in multiple locations in a wilderness by a single individual or entity is counted as a single action. For example, concurrently stocking fish in multiple lakes across a wilderness counts as a single trammeling action.

- Unauthorized actions that occur outside of wilderness intended to manipulate the biophysical environment within wilderness count as trammeling actions. For example, the introduction of game species outside of wilderness with the intent that they travel into wilderness, when not explicitly authorized by the agency based on the results of a minimum requirements analysis (MRA), counts as a trammeling action.

- Persistent Structures

- To be counted as a trammeling action, a persistent structure must be intended to purposefully alter, hinder, restrict, control, or manipulate the "the earth and its community of life." Examples of persistent structures that would be counted under this measure include, but are not limited to fish barriers, dams, water diversions, guzzlers, bat gates, or fencing (e.g., wildlife or cattle enclosure areas). Each unique, unauthorized persistent structure that manipulates any component of the biophysical environment is counted for each year that it exists.

- The unauthorized installation of a persistent structure that alters the biophysical environment in wilderness (e.g., an impoundment and irrigation tubing for illegal marijuana cultivation, unauthorized installation of fencing) is counted once as a trammeling in the year that the installation occurred, and once per year subsequently as long as the structure persists. The installation and existence of the structure in the first year are not double counted as two trammeling actions. Persistent structures that are no longer functioning are not counted as a trammeling if it can be demonstrated they do not alter or manipulate any component of the biophysical environment (e.g., fencing previously used to form a cattle exclosure that has fallen down).

- Other Clarifications

- Evidence of an unauthorized trammeling, as opposed to an agency employee witnessing the trammeling action in progress (e.g., the discovery of an abandoned marijuana grow site), is sufficient to count as a trammeling action.

- Related yet distinct types of actions count as multiple trammeling actions. For example, an unauthorized state wildlife management project that involves introducing game species and controlling predators via increased bag limits count as two trammeling actions. The magnitude or effects of these actions does not have any bearing on the number of trammeling actions reported.

Step 3: Enter data in NRM and the WCMD. Track trammeling actions annually and enter them into the NRM-WCM application for each fiscal year. NRM-WCM will sum the counts of all unauthorized trammeling actions to generate an annual value. Local units must then validate the value generated by NRM-WCM and correct records in NRM as necessary. Once validated, enter the annual value in the WCMD. The WCMD automatically calculates 3-year rolling averages based on the annual values. The measure value is the 3-year rolling average number of trammeling actions.

Caveats and Cautions

This measure depends on a combination of incidental, chance encounters and the amount of effort spent to find unauthorized actions. For instance, the reintroduction of game species by a state agency without explicit authorization might be incidentally discovered through media reports. Conversely, water diversions associated with a marijuana grow site are typically discovered because of law enforcement investigations, though such a use could also be discovered after an incidental report from the public. Due to the unpredictable nature by which unauthorized trammeling actions and persistent structures are discovered, information about the method and level of effort required for a given discovery should be documented in the WCMD to allow for an understanding of data adequacy when comparing results across multiple years of reporting.

When deciding which specific 3 years of data to include to calculate the rolling average for this measure, always defer to the highest data adequacy available (section 1.2.3 in part 2). Ideally the data with the highest degree of adequacy will also be the most recent data collected, but this might not always be the case.

Data Adequacy

Data adequacy is medium or low, though this should be verified and documented by the local unit. It may not be feasible to reliably gather all applicable data, and knowledge of some unauthorized actions may rely on incidental, chance encounters. Data quantity is partial and data quality is moderate. Additionally, knowledge of unauthorized actions is dependent on field or law enforcement presence and the amount of effort put into identifying unauthorized actions, which should be documented in the WCMD.

Frequency

Data are compiled, analyzed, and entered into the WCMD annually due to the variable nature of trammeling actions.

Threshold for Change

The threshold for meaningful change is a 5-percent change in the 3-year rolling average number of unauthorized actions and persistent structures. Once there are five measure values, the threshold for meaningful change will switch to regression analysis. A decrease in the 3-year rolling average beyond the threshold for meaningful change results in an improving trend in this measure.